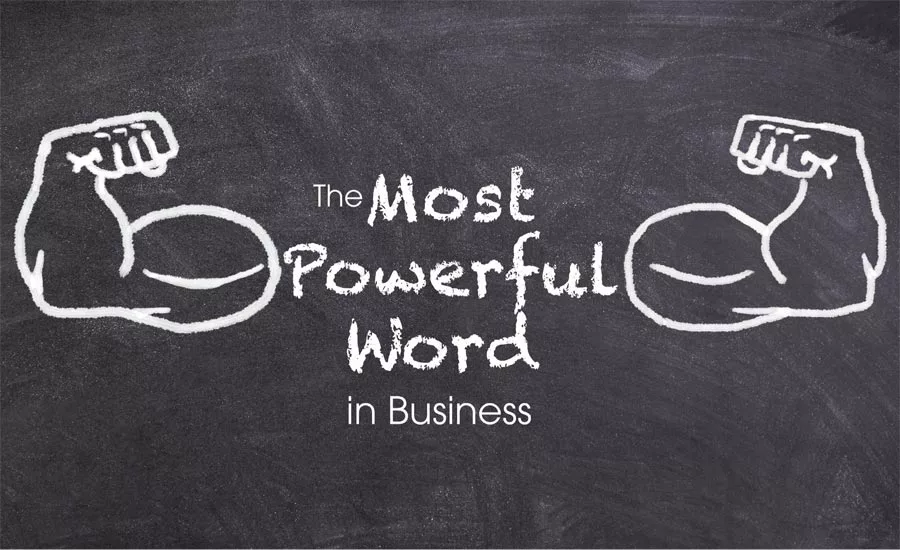

The Most Powerful Word in Business

Almost one year after my working career in restoration started, I was baptized by accepting a request to look at a boat fire. I had absolutely no knowledge of marine vessels, how they were constructed or what the component materials were, let alone how they react when they burn. Moreover, I had very little experience with fire and smoke restoration procedures in general. But, as a young twenty-something restorer with a fairly robust ego, I was perfectly qualified. At least in my own mind.

As I toured the thirty-six-foot cabin cruiser valued at just under a quarter million dollars, the adjuster and owner peppered me with questions about our ability to clean and deodorize the boat, whether we could have it completed by the end of the summer season, and if we could do it without exceeding the reserve already set by the carrier. Not being one to back down from a challenge, I poised myself in the most professional tone and said yes to everything.

Right about now, I’m sure you can imagine where this story is going … and you are correct. I grossly underestimated the complexity of the project and the amount of time associated with the scope of work that needed to be done. Consequently, we delivered the project almost three months late at more than 300% over budget. We lost our shirts and then some! Needless to say, this project taught me significant lessons about the importance of saying no.

The first thing I learned was, when looking at a project for the first time, you must pay attention to the red flags. When faced with a new opportunity that has the likelihood of a less-than-desirable outcome, there are warning signs everywhere. You just need to train yourself to identify them.

Such was the case with the boat fire project. I failed to recognize that I was being called to look at it months after the actual fire had occurred. I chose to ignore the fact that I was the fourth restoration contractor called to the job, and I was oblivious to the laundry list of unreasonable requests being made by the owner and insurance adjuster. The fact that I was making commitments to services my company had little to no experience with was just icing on the cake.

The problem begins with the fact that the first thing we expect of our estimators and project managers is to get the sale! And, we work in a service industry where our instinct is to serve with the word yes. To avoid these situations, I recommend getting the entire team together and developing your own list of red flags. I have done this in each of the Restoration Estimating classes I have instructed over the past eight years, and the list is always very interesting. The red flags that top my list of personal favorites are lawyers, interior designers, and divorced insureds.

Despite how obvious banners of caution can be, restorers will still proceed under the premise of capability more times than not. Whether driven by pride, greed, or simply the desire to help those in need, the tendency to ignore red flags is always great. This leads me to my second lesson learned, which is the fact that just because you CAN do something, doesn’t mean you SHOULD.

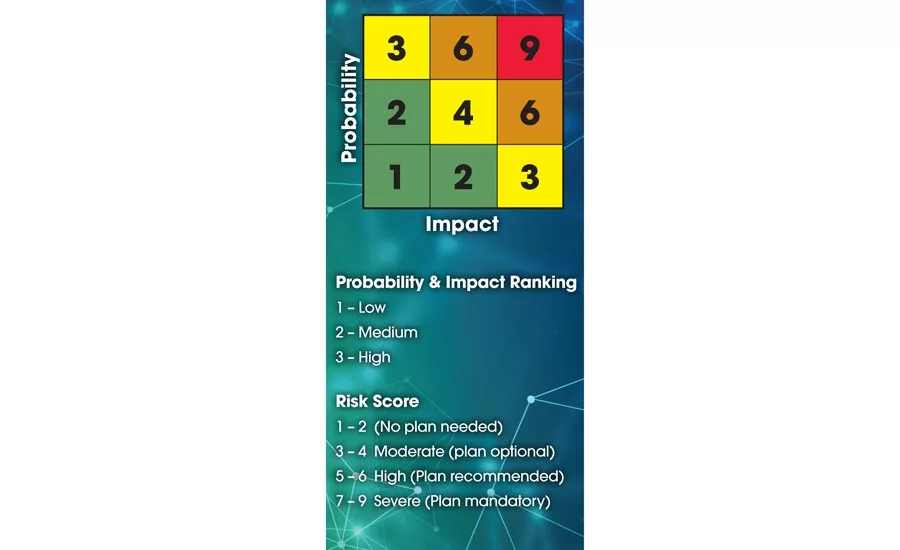

Putting on the brakes at this stage of the game requires a deeper understanding of the red flags and the risk they pose to the project and the company. This means a risk assessment is necessary. We don’t need a sixteen-cell risk analysis matrix and a degree in actuarial science to get a good idea of whether the job is going to be a loser or not. However, we do need at least a fundamentally sound opinion of the probability and impact of the potential risks involved with the project.

If the boat had sunk during our restoration efforts, the impact to the project certainly would have been catastrophic; however, the likelihood of that happening was slim, especially since it was sitting in a dry dock next to the marina. On the other hand, the probability of the scope of the project being wrong was high since we had never done a boat fire loss job before. The impact of that having a negative effect on the project was also high, putting things in the “show stopper” quadrant.

Best practices and a little common sense kick in at this point, telling us we need a plan to mitigate either the probability or the impact of the significant risks before moving forward. This is where most folks fall short. This is also where the power of saying no really comes in handy. Saying no at this point in the project virtually eliminates risks, sometimes by the customer taking them off the table all together, provided they really want you to do the work.

Imagine if I had told the boat owner and insurance adjuster that we had no experience with boat fires and were reluctant to move forward? Considering the other contractors who had already looked at the job, I might have been their last resort, and instead of making unreasonable requests, they might have offered flexible options to incentivize me to take the job. That puts the risk evaluation into a much different perspective and reinforces the power of saying no.

Even with the red flags identified and the risk assessment completed, saying yes or no to a project comes down to priority, and there are several things that can drive priority. Whether it is work load, cash flow, referral source, market share, reputation, or any number of valid business objectives your company sets out to accomplish, there is something driving the decisions to pursue certain types of work.

Using your company’s priorities as a guide is the conservative approach and generally keeps us out of trouble. It is when these priorities are compromised that we see poor decisions being made with projects we had no business pursuing.

This brings us to the last lesson I learned, something that would serve as confirmation that saying no was the correct course of action: to consider the unintended consequences of saying yes.

This permission slip to say no is nothing more than a “what if?” question and answer with yourself. Had I applied this principle to the boat fire, I probably would have asked myself, “What if this job takes longer than it should?” and thought about it tying up my best technicians during our busiest time of the year. Not only would I have extended labor costs, but I would also have significant opportunity costs as well. This exercise should make your priorities and course of action crystal clear. I know it would have for me when it came to the boat loss.

Restorers must learn from the lessons of the past. One of the fastest and most expensive ways to fail in business is to try to be everything to everybody. Understanding when to say no can keep you from falling into that trap. Learn to identify the red flags, evaluate the risks, and consider the unintended consequences of your decisions and the impact they have on your company’s priorities.

The word no could arguably be the most powerful word in business. It draws a necessary line in the sand, keeps you true to your principles and values, and allows you to stay focused on your goals.1 Even in a business where saying yes is a natural part of the job, this two-letter word can frequently produce better results than you might think.

1 “The Power of No”, Judith Sills, PH.D., Psychology Today, June 9, 2016

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!