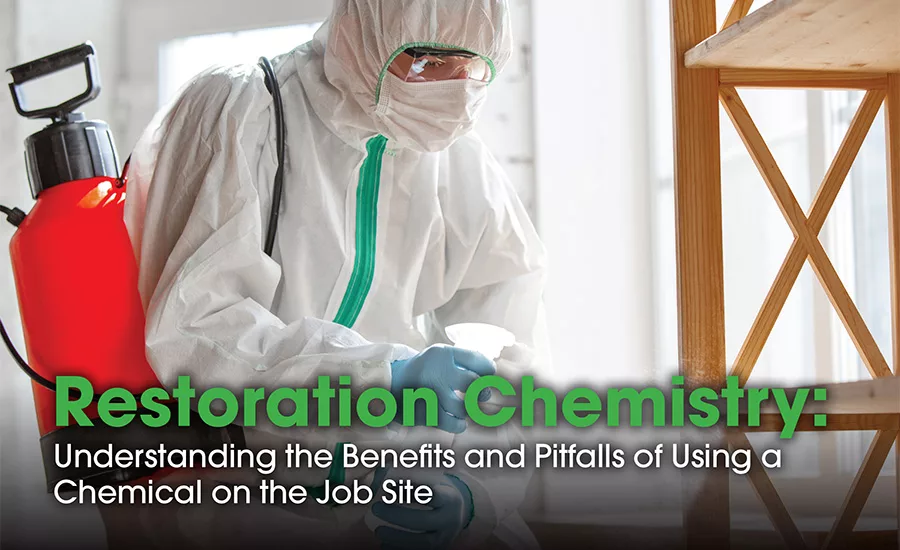

Restoration Chemistry: Understanding the Benefits and Pitfalls of Using a Chemical on the Job Site

Have you ever stopped to wonder what role chemistry plays in our professional lives as cleaners and restorers? To get a sense, all you have to do is go out to your shop or warehouse and stop in front of the shelf, cabinets, or storage room that has all your miscellaneous bottles, cans, bags and containers of miscellaneous chemicals. And these are just the leftovers! They are the residual portion of one-off products that were purchased for a specific project, partially used, and thought to be too valuable to dispose. Surely (the thinking goes), we will be able to use this at some point in the future.

So, there they sit. The usual suspects include:

- Partial cans of paint

- Samples of cleaners

- Half-full bottles of various disinfectants that indoor environmental professionals insisted be used on a specific project

- Containers of glues and mastics that were never properly cleaned off before they were stored; so now the caps/lids are permanently adhered to the container

- So much more.

And, of course, these items relegated to the “shelves of cast-off chemicals” are but a fraction of the volume of chemicals that are used on a regular basis. Carpet cleaners, soot removers, disinfectants, sealers, green cleaners, solvents, pre-wetted wipes, hand sanitizer, and restroom soaps are all regularly purchased and kept in inventory; oftentimes by the 5-gallon bucket or pallet load.

A Lack of Chemical Awareness Collides with a Pandemic

Unless the company’s internal safety programs are fairly robust, it is easy to get lackadaisical about chemicals in the shop and on the job. Team members are so used to working with various chemical products, that they barely ever read a label, and hardly ever take the time to look at the safety data sheet (SDS). Let alone understand it. “We use what we have always used, and everybody is happy with it,” is a typical response to questions about restoration chemicals.

Then, everybody in the restoration industry was rudely shoved into the age of the COVID-19 pandemic. Suddenly, clients were asking questions about disinfectants, effective cleaning of touchpoints, and whether chemicals were “EPA-approved.” The fact that the virus caused the COVID-19 disease was so new that no chemical had been tested against this specific organism, which meant that restoration contractors had to scramble. They had to quickly learn about the Environmental Protection Agency’s registration process for chemicals, as well as the EPA’s “Emerging Pathogens” program. That way, intelligent answers could be provided to client concerns and marketing pieces for COVID-19 related services.

*Click the image for a larger version

Putting the Spotlight on Chemical Education

Coincidentally, the scramble for chemical information throughout the restoration industry coincided with an offer to put together a series of articles for R&R magazine. This would be related to chemical use in all the major aspects of restoration work: cleaning fire damaged buildings, dealing with water intrusion, mold remediation, and specialty services, such as meth contamination or forensic restoration. As a result, look for additional articles regarding chemical use in the next few issues.

Since this series of articles will focus on typical restoration scenarios, but also offer some examples from unusual events (such as responding to a major steam leak with residual boiler treatment chemicals on the interior building surfaces), it is important to note that the author does not work for a chemical company and has no direct financial ties to any such entity. However, 42 years in the safety and health field, with over 25 of those years specializing in serving the cleaning and restoration industry, has brought the author into contact with many of the major chemical manufacturers that service this industry.

Chemicals to Deal with the Current Industry Gorilla — The Pandemic

As noted previously, the declaration of COVID-19 as a global pandemic sent people scurrying to obtain chemicals that they could utilize to “kill” the virus. The problem was that there was no analytical data to show that any chemical was effective in killing the specific virus that causes the COVID-19 disease (designated SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization). The identified virus was so new that no tests of chemical products had been conducted. Therefore, for many months after the pandemic declaration, there was no EPA-Registered disinfectant that could say it was proven to kill the new virus on their label.

Although such a situation sounds disturbing, it is not unprecedented by any means. Because there is a known time lag between identifying infectious agents and having product manufacturers submit testing data (which proves a disinfectant’s efficacy against those newly discovered microbiological contaminants), the EPA has a system to deal with that scenario called the Emerging Pathogens Program. Those government rules allow chemical manufacturers to compare their existing test data with similar classes of organisms as the new threat and show that they should be effective. In those cases, the EPA “approves” the use of various products that have been shown through their previous registration data to be effective against the type of microorganism causing the problem. That is why many of the government advisory documents utilize the term EPA-approved disinfectant as compared to EPA-registered disinfectant.

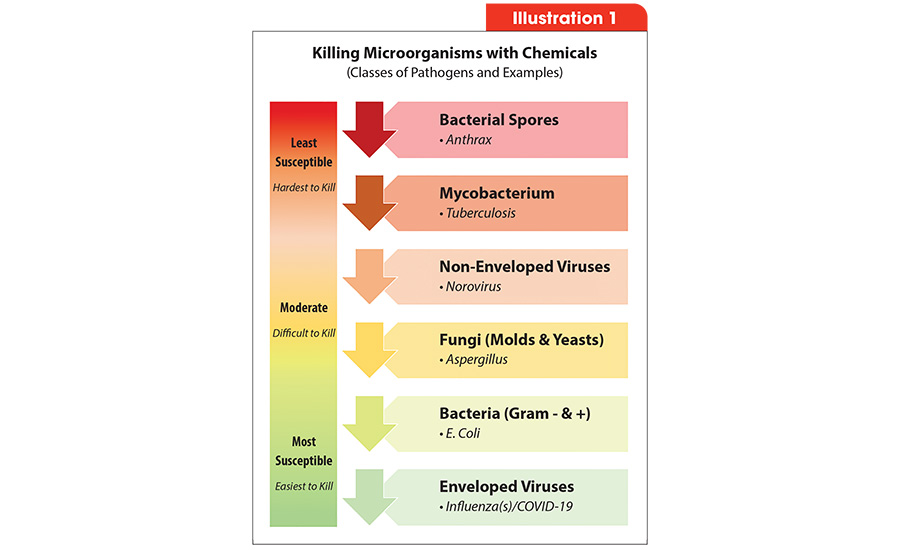

As part of the EPA’s emerging pandemic program, they keep track of the products where the manufacturers have evidence of effectiveness in killing similar microorganisms. Illustration 1 explains this in a chart format with some specific examples.

The products that are effective against similar organisms (in this case, an enveloped virus) are posted on the EPA’s List N, the compilation of products approved for use as a disinfectant during COVID-19 pandemic. Because of the intense interest in whether specific products are effective or not, the EPA updates its List N every few days and prominently posts a link to it on its main website.

Understanding the EPA Terminology

It is critical that in the process of assisting clients in dealing with concerns about disease transmission during the pandemic, the company isn’t put at risk because of loose language about the type of services to be provided or the effectiveness of those efforts. This concern was highlighted in a joint document put out by the Restoration Industry Association (RIA), the Institute for Inspection, Cleaning, and Restoration Certification (IICRC) and the American Hygiene Association (AIHA). That document1 notes:

Clients continue to turn to restoration professionals to assist them in properly responding, as the coronavirus pandemic, referred to as “COVID-19”, moves into different phases, to include business re-opening. In such circumstances, it is imperative that restoration professionals be clear about what their services can, and cannot, accomplish for the client.

One term in particular that shows up often (even in government documents which can cause problems for restoration and cleaning contractors) is the verbiage to “clean and disinfect buildings.” A frequently seen variation is “clean and sanitize the building.” These are general terms used to describe enhanced cleaning procedures recommended during times of epidemics/pandemics. However, since the words “disinfect” and “sanitize” have a variety of specific and technical definitions (described by various rules and regulations for food service, agricultural producers, manufacturers of medical devices, and other industries), it is not wise to use those terms in advertising, discussions with potential clients, or contracts.

Using such terms means that the contractor and client may have very different ideas about what the end result is supposed to be. Specifically, a contractor who uses the term “disinfect” or “sanitize” may be committing to a specific level of reduction of microorganisms. In one of the consumers bulletins2 on the EPA’s website, they explain that:

Surface disinfectant products are subject to more rigorous EPA testing requirements and must clear a higher bar for effectiveness than surface sanitizing products. There are no sanitizer-only products with approved virus claims. For this reason, sanitizers do not qualify for inclusion on EPA’s List N: disinfectants for use against SARS-CoV-2.

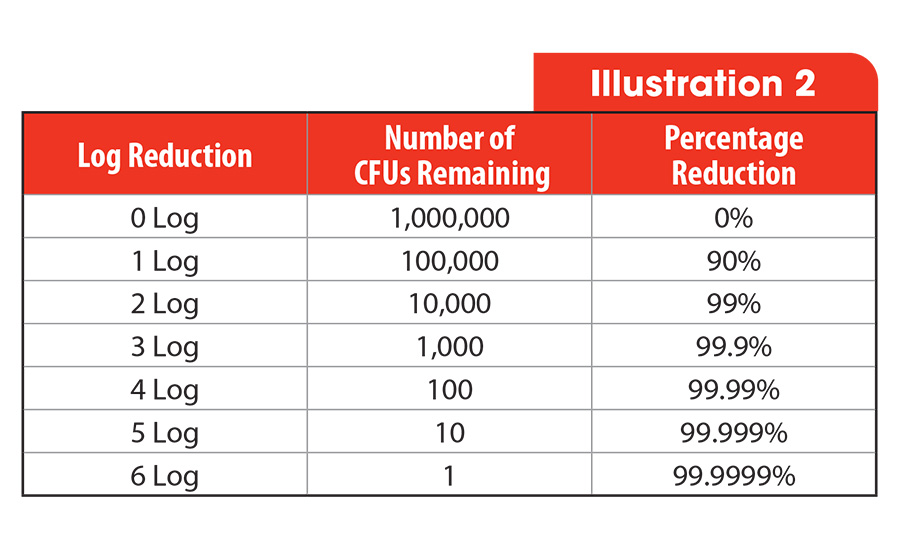

The EPA goes on to define sanitizers as chemical products that can kill at least 99.9% of tested microbiological contaminants on hard surfaces (that percentage should go up to 99.99% of the tested contaminants on surfaces used for food service). As noted in the EPA’s consumer bulletin quoted above, disinfectants are stronger. For disinfectants, the EPA requires the manufacturers to show that the product kills 99.999% of selected microorganisms on hard, non-porous surfaces or objects.

Illustration 2 is a chart that makes sense of all the decimal points and shows the stark difference between the sanitizer and a disinfectant. At 99.9% reduction in viral contaminants achieved by a sanitizer, one thousand viral particles would still be left alive on the surface that started with 1 million colony forming units (CFUs). Using the same cleaning process with a disinfectant would ensure that no more than 10 viral particles survived.

Given the regulated nature of disinfectants and the stringent surface testing that goes on in certain industries related to that term, it is recommended that contractors offering COVID-19 services intentionally use terms that describe the actual activity (such as “clean surfaces by wiping touchpoints” and “apply a disinfectant”) in their contracts and marketing information.

Beyond The Pandemic

While many restoration contractors were busy providing pandemic-related services at the time this article was prepared, the hope is that COVID-19 will eventually fade into history much like SARS and swine flu. Although the demand for the broadscale use of disinfectants may diminish, the need for restoration contractors to understand the risks and benefits of using chemicals to assist them on their projects will never disappear. The next installment of this series will focus on chemicals for mold remediation.

- The COVID-19 Pandemic A Report for Professional Cleaning and Restoration Contractors, Fourth Edition, July 2020

- What’s the difference between products that disinfect, sanitize and clean surfaces? Found at: https://www.epa.gov/coronavirus/whats-difference-between-products-disinfect-sanitize-and-clean-surfaces

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!