Burnout in the Restoration Industry | Part 1

Editor’s Note:

This is the first article of a multi-part series on employee burnout in the restoration industry. Part one introduces the nature of burnout and summarizes findings from a study on burnout in the restoration industry. Part two begins a discussion on things restoration companies can do to manage one of the most complicating factors for burnout among restoration professionals - workload. Part three advances the conversation and discusses what restoration professionals can do at the individual level to manage workloads more effectively.

Since the 1990s, experts have been declaring burnout levels are reaching epidemic proportions among North American workers (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). Since that time, most people would probably agree that work related stressors have only intensified with the proliferation of metrics, technology, and the need to be “on” all the time. A recent study by Gallup (Wigert & Agrawal, 2018) surveyed 7,500 full-time employees in the United States and reported that 67% of the respondents experienced feelings of burnout on the job. Another study by Deloitte (2018) surveyed 1,000 full-time professionals in the United States and reported that 77% of respondents said they had experienced burnout in their current job. In addition, the World Health Organization announced it would be revising their definition of burnout in the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases, effective Jan. 1, 2022. One of the primary changes will be how burnout is classified—this revision will involve a change in classification from “a type of psychological stress” to a “syndrome.”

Disaster restoration professionals operate in a niche of the construction industry that is inherently stressful. Their work often demands being on call and working long hours under stressful and dangerous conditions following fires, floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, tornadoes, and a variety of other catastrophic events to structures. In addition, there are performance demands driven by metrics related to response times, project completion rates, customer service, and many other factors. Such conditions make restoration professionals more susceptible to burnout; therefore, it is important to understand the nature of burnout and how the effects may be mitigated.

"Burnout is defined as a crisis in a person's relationship with their work, as well as a syndrome of three distinct feelings that comprise the dimensions of burnout: exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy (Masiach & Leiter, 1997)".

The reasons for burnout can be complex and are addressed at length in many studies and books that have been published on the topic over the past few decades. Many have debated the reasons for burnout, whether occasional feelings of burnout can be good for someone, the complexity of burnout and the degree to which non-work factors may contribute to feelings of burnout on the job (and vice-versa), and where future inquiries into the subject should focus—among other topics. While many of these factors are still being debated and explored, there are many things scholars and professionals have come to understand about burnout and agree upon. Specifically, it is important to understand that some industries have higher burnout rates than others and that contextual factors such as organizational culture and the capacity to cope with stress within individuals vary widely.

Regardless, there is much for an industry to gain by having a deeper understanding of employee burnout among professionals and to explore strategies for improving the health and lives of its members. The primary goal of this article is to discuss the nature of burnout, share findings from a recent study on burnout within the restoration industry, and begin a practical discussion related to how we, as an industry, can seek to thrive with the inherent challenges the industry faces. We hope many productive conversations develop from this article.

Restoration is a great industry that does great work for the great people of our society. It is inherently challenging and stressful, but rewarding for those who enjoy working hard and doing good work for good people in need. This article seeks to candidly discuss the challenges of burnout for restoration professionals and begin a productive conversation on how we, as an industry, can do our work in a rewarding, enjoyable, productive, and effective manner.

Burnout

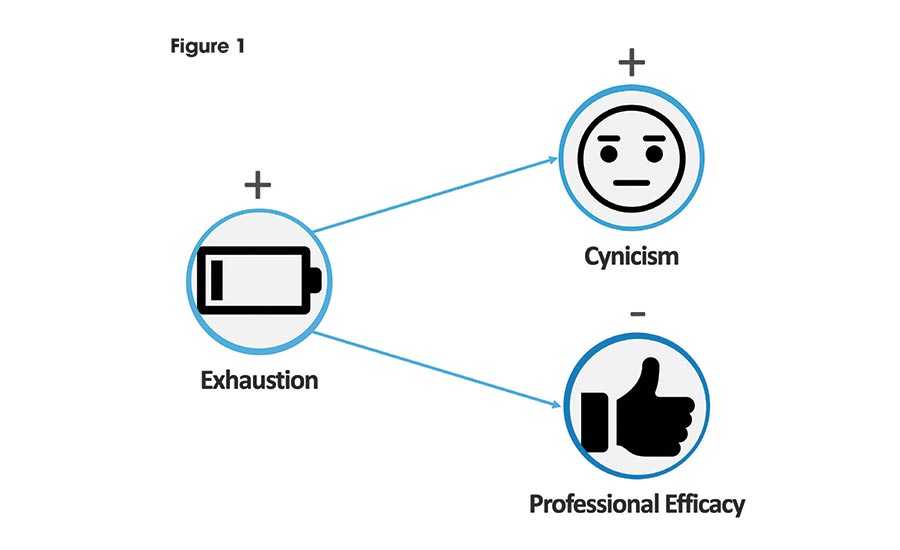

Burnout is defined as a crisis in a person’s relationship with their work, as well as a syndrome of three distinct feelings that comprise the dimensions of burnout: exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

Dimensions of Burnout

The three dimensions of burnout help us understand the primary characteristics of burnout and provide insight into the nature of the burnout experience.

- Exhaustion: The feeling of being overextended and physically and emotionally drained. “[It] is the first reaction to the stress of job demands or major change” (Maslach & Leiter, 1997). When someone is feeling exhausted, they lack energy and are unable to unwind and recover (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

- Cynicism: Leads to people developing a distant attitude toward work and the people surrounding them at work. In a sense, it is a defense mechanism that is deployed to protect oneself from exhaustion and disappointment (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

- Professional Efficacy: Relates to feelings of effectiveness and adequacy regarding a person’s work. Accomplishment is vital and it is important for professional development and self-confidence. As someone loses confidence in themselves others lose confidence in them (Maslach & Leiter, 1997).

Worklife Context

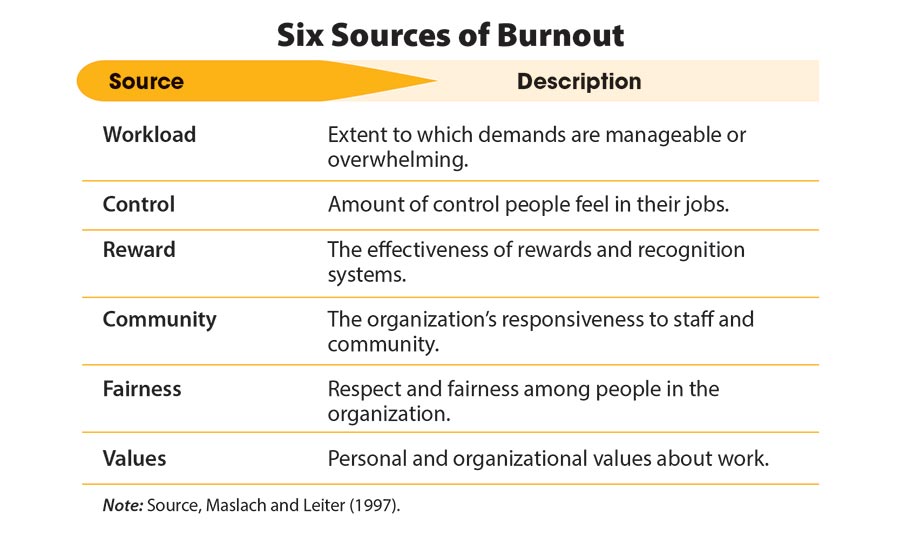

(Sources of Burnout)

Equally important to understanding the components of the burnout phenomenon it is essential to examine the primary sources that influence exhaustion. There are six sources of burnout that mediate feelings of exhaustion:

Summary of Findings from a Recent Study

A recent study on burnout conducted by two of this article’s authors, Dr. Avila and Dr. Rapp, sought to explore the nature of burnout and worklife context (sources of burnout) among restoration industry professionals (Avila & Rapp, 2019). We distributed a survey that consisted of a demographic questionnaire, the Maslach Burnout Inventory, (MBI), the Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS), and a set of exit questions that gauged respondents’ turnover intentions. A total of 318 respondents completed the entire survey.

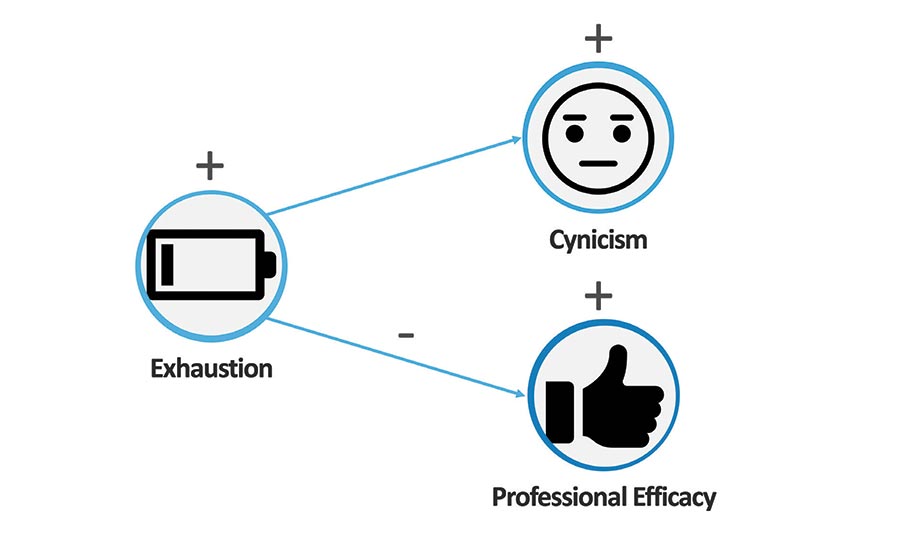

The results on burnout revealed that, when compared to other industries, restoration professionals were experiencing higher levels of exhaustion, cynicism, and professional efficacy. The researchers had not anticipated this interesting finding. The model, as discussed in earlier in this article, suggests that as exhaustion increases, cynicism increases, and professional efficacy decreases. Why would restoration professionals have increased professional efficacy when the mediating factors suggest they should be experiencing the opposite? Is it their resilience? While years could be spent studying this to find an explanation we aren’t going to be doing that. It is time for a practical discussion. We know restoration professionals experience burnout so it is imperative for us to discuss why we think this is the case and what we (professionals and employers) can do to mitigate the effects of burnout.

"Results of the six sources of burnout found that workload was the only source having a statistically significant effect on exhaustion for restoration professionals."

Moving forward, an important part of the discussion on burnout should explore the reasons restoration professionals would experience burnout in a manner that is so unique and different from other industries. What factors do we think are contributing to this dynamic? Could findings on the sources of burnout help us understand how and/or why restoration professionals would experience burnout in the manner the study has revealed? Could the amount of hours restoration professionals work be contributing to them having a high sense of professional efficacy? Could factors related to the number of years they have worked in the industry influence their sense of professional efficacy?

Results of the six sources of burnout found that workload was the only source having a statistically significant effect on exhaustion for restoration professionals. From this point, the researchers had to look to answers respondents provided in the demographic questionnaire at the beginning of the survey. There were two primary data points in the demographic questionnaire where the researchers discovered correlations to workload:

- Number of hours worked: Respondents self-reported the number of hours worked and the average was 52 hours per week; however, some respondents reported working more than 80 hours per week. As the number of hours increased, the respondents were move likely to report a heavier workload.

- Number of subordinates: Respondents self-reported the number of subordinates supervised and this finding was negatively correlated with perceptions of workload. As the number of subordinates supervised increased the respondents were more likely to report a heavier workload.

While workload, in itself, can involve many factors, we will explore ways in which it can be managed effectively at the company and individual levels. In the second part of this series, we will start to discuss how to manage the burnout.

Special Thanks

The authors wish to extend special thanks to the members of Business Networks who have graciously shared their experiences, NextGear Solutions who opened the door for public discussion on these topics among restoration professionals, and other industry professionals who have engaged us on the development of the study throughout the entire process. Thank you for the support, feedback, and valuable insight.

References:

Avila, J., & Rapp, R. (2019, January 2). Restoration industry burnout study. https://doi.org/10.5281/zendo.3404108

Bakker, A., & Demerouti, E. (2014). Job demands-resources theory. In C. Cooper, & P. Chen (Eds.), Wellbeing: A complete reference guide (pp. 37-64). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Deloitte. (2018). Workplace burnout survey: Burnout without borders. New York, NY: Deloitte. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/about-deloitte/articles/burnout-survey.html

Huberty, C. (1984). Issues in the use and interpretation of discriminant analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 95(1), 156.

Lee, R., & Ashforth, B. (1996). A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(2), 123.

Leiter, M., & Harvie, P. (1998). Conditions for staff acceptance of organizational change: Burnout as a mediating construct. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 11(1), 1-25.

Leiter, M., & Maslach, C. (2011). Areas of worklife survey: Manual (5th ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2(2), 99-115.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. (1997). The truth about burnout. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S., Leiter, M., & Schaufeli, W. (2016). The maslach burnout inventory: Manual (4th ed.). Menlo Park, CA: Mind Garden, Inc.

Maslach, C., Leiter, M., & Schaufeli, W. (2008). Measureing burnout. In Cooper, & S. Cartwright (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organizational well-being (pp. 86-108). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pines, A., Aronson, E., & Kafry, D. (1981). Burnout: From tedium to personal growth. New York, NY: Free Press.

Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2004). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: Preliminary manual (1.1 ed.). Utrecht, NL: Occupational Health Psychology Unit, Utrecht University.

Schaufeli, W., Salanova, M., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a confirmative analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92.

Seashore, S., Lawler III, E., Mirvis, P., & Cammann, C. (1983). Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices. Hoboken, NJ, US: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tonidandel, S., & LeBreton, J. (2013). Beyond step-down analysis: A new test for decomposing the importance of dependent variables in MANOVA. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(3), 469.

Wigert, B., & Agrawal, S. (2018). Employee burnout, Part 1: The 5 main causes. Washington, D.C.: Gallup. Retrieved from https://www.gallup.com/workplace/237059/employee-burnout-part-main-causes.aspx

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!