Innovations in Restoration: Laser Cleaning

Laser (n.): A device that produces a narrow and powerful beam of light that has many special uses in medicine, industry, etc.

Media blasting is a popular technique very effectively used to blast away stains from soot, mold, and Mother Nature. Now, a company in Chicago is introducing restorers in the U.S. to another technique that’s already widely popular abroad: laser cleaning.

In May of last year, the State of Oklahoma began the process of restoring its state capitol. This summer, that included cleaning trials to remove a variety of stains on the exterior façade. While stains are natural for limestone, a very porous sedimentary rock, a past attempt to seal the stone has created a very difficult restoration hurdle.

|

Pros of Laser Cleaning: • Eco-friendly • No abrasive media • No damage to surface • No debris • Compact & lightweight • No noise disruption Cons of Laser Cleaning: • Requires carefully tuning • Price point • Surfaces need different photo-absorptive properties |

“There are two basic kinds of stains. The first is natural, biological growth that occurs in limestone,” explained Trait Thompson, project manager of the Oklahoma Capitol Restoration Project. “The more difficult stain we’re dealing with it is due to a chemical moisture sealer applied on the building, we think, 25 to 30 years ago.”

Thompson believes instead of repointing mortar and finding other solutions for moisture infiltration in the past, a sealer was sprayed on the building. That sealer sunk into the limestone.

“It was really bad form, you are not supposed to do that,” Thompson said. “We have a problem with red dirt here in Oklahoma, and when it blows it attracts to that sealer. So now we have these red splotches all over the building, particularly on the south façade.

At the start of the cleaning trials, a number of cleaners, products, and techniques were used to try to clean out those set-in stains. According to Thompson, however, the results were mixed and nothing “really great” had shown up on their radar. Then came the laser cleaning trial in August.

Bartosz Dajnowski, from the Conservation of Sculpture & Object Studio (CSOS) in Chicago, Ill., performed the trial, which was captured on video. You can check it out on www.randrmagonline.com. CSOS is a family business that started doing laser cleaning more than 13 years. Dajnowski says they were the first company in the world to use lasers to clean massive structures, like a 25,000 square foot façade in 2004, which was a world-record project at the time. They also cleaned a 3,500-year-old Egyptian obelisk in New York City, and are currently cleaning marble on the façade of the U.S. Supreme Court. CSOS has primarily used lasers from companies abroad, particularly Europe. However, that created logistical problems if a laser needed to be serviced.

Through his expertise, training, and education, Dajnowski created GC Laser Systems. His expertise started in art conservation science, and expanded from there. He even spent time at a military training facility in Poland where laser systems are designed for everything from civilian use to art cleaning. There, he also learned how to service some laser equipment in the field and started designing his own systems for a variety of applications. Today, he has patents pending worldwide. Plus, he’s started to market these systems in the disaster restoration realm.

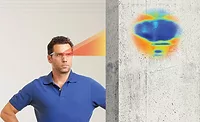

“Laser cleaning relies on taking advantage of the simple fact that every material on earth absorbs light, and they absorb light differently based on things like their color or physical composition or chemistry; basically their photo-absorptive properties,” Dajnowski said. “It has huge applications in disaster response, especially fire restoration. Anything that has soot on it, that’s one of the easiest things for the lasers to deal with,” Dajnowski explained.

An easy way to explain the absorption and reflection of light is to think about a black car in the summer. That surface gets hot much more quickly than that of a white car because the black absorbs while the white reflects.

To clean a surface, Dajnowski first targets what the contaminant is that needs to be removed, and looks at its absorptive properties. That means knowing what wave length of light and what parameters it would absorb the laser light. Ideally, the material beneath the stain does not absorb the same parameters of the contaminant that needs to be removed.

Ablation is one of the thresholds that needs to be identified in laser cleaning projects. Dajnowski defined ablation as the “parameter at which the contaminant we are targeting literally vaporizes off a surface.”

“The molecules and the atoms of the contaminant, let’s say it’s carbon – it’s fire damage, they get so excited by the energy they absorb, the bond gets broken and atoms expand at such a fast rate at a micro level that it’s like inflating a beach ball at the rate of an air bag. So the carbon just separates off the surface and breaks apart,” he said. “It literally vaporizes off the surface.”

Unlike mechanical cleaning blasts off the soot, lasers excite it to the point it separates off on its own. Sometimes, you even hear a buzzing or popping sound when the sound barrier is broken at a micro level. There can also be chemical changes on the surface – you can literally break down the chemical makeup of a contaminant. There are also potentially photo-thermal effects.

“Most people have the wrong assumption that when lasers are used, we are burning the surface, and that’s just not true at all,” according to Dajnowski. He explains this concept like putting your finger in a candle. Leave it in the flame for more than a second, and you’ll get burned. However, if you just quickly swipe your finger through the flame, you won’t get burned. In laser cleaning, it’s the same concept. It’s not a solid steam like a laser pointer, its pulses lasting nanoseconds. Therefore, you might have a one or two degree surface temperature difference, maximum.

“It’s not a magic wand tool,” he said. “You can’t just point it at something and expect it to work. The settings you used for one material might not work on another material, and might actually damage it. So there is some level of understanding of the science behind it and the requirements to safely do it.”

Talking pricing – be prepared for a big difference between laser cleaning equipment, and that for media blasting. Laser cleaning equipment can run into the tens of thousands of dollars because the technology is expensive. However, Dajnowski is putting together rental and leasing options. Plus, they do not have parts that will wear out. It runs out of a standard outlet, does not require the purchase of media, etc. It’s set as-is.

Regarding the Oklahoma Capitol Restoration Project, both the project manager and architectural firm are pleased with the outcome of the laser cleaning trials.

“The laser cleaning was very effective on the most apparent soil you see when you look at the building – the orange/brown windblown dirt,” remarked Julia Manglitz, associate principal at Treanor Architects. “Because it was a light-colored surface, and different colored soil, it was a good process to consider. Because it’s only a surface treatment and can’t penetrate into the stone, it doesn’t affect the penetrating sealer.”

Manglitz said nothing else really worked for penetrating the old sealer, including wet chemical processes and micro abrasion.

Now, the project is entering the design phase. Thompson is working with Treanor Architects to define the scope of work and present possible courses of action to the legislature.

Vance Kelley, principal at Treanor Architects, said the current scope and money would mean work would be done in two or three years. However, there’s enough work that if additional funding was approved, Thompson said the project could carry on for six years.

“Once [the legislature] determines how much they want to spend, the work will be bid out, and we will follow it through to completetion,” Kelley said.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!