Behind the Curtain: A Look into the World of Textile Restoration

While not every contents restoration operation requires a massive space, some do. This is an overview of CRDN’s massive main plant.

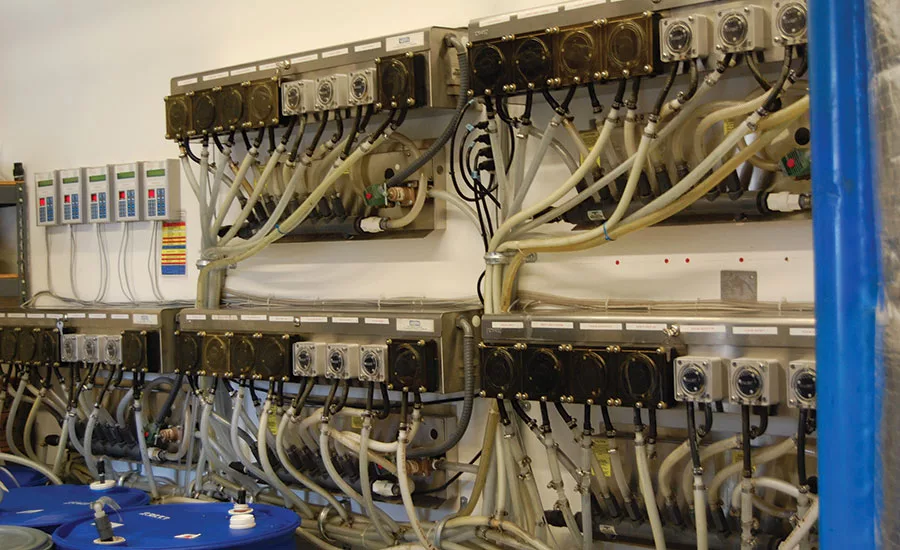

A modern textile restoration facility will include machines that are based on various solvents.

Storage areas are also important in contents restoration. In this case, clothes are carefully inventoried hung together or boxed up to be stored until the owner is ready to have them returned. In some cases, CRDN uses a locked vault room to store more high-end items.

A special machine helps her carefully pleat drapes during restoration.

Shoes are dried on a special rack during the restoration process.

In this image, two workers use a large flatwork iron to effectively press a large textile, like a sheet.

These are finishing stations, where a garment is teamed or pressed.

There’s an old saying that when all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. When it comes to restoring garments and other textiles involved with an insurance claim, a full tool box is required to successfully handle dozens of types of contaminants, hundreds of types of materials, and thousands of types of items.

While most of us are familiar with a retail drycleaning experience (you take your clothes to the counter, and then return a few days later to receive them freshly pressed and on hangers, like magic), today’s textile restoration is highly sophisticated and requires a scientific approach that combines specialized equipment and experienced personnel.

A decade ago, when restoration drycleaning was becoming an accepted part of the claims industry, the term “drycleaning” held certain connotations: expensive, limited, reactionary. These perspectives were based on everyday over-the-counter experiences with retail drycleaners, and rightly so.

Even today as “textile restoration” is the common term, there is still some mystery about what happens to garments and other fabric items affected by smoke, soot, water and other contaminants.

As non-drycleaners have tried to add textiles to their existing restoration services, many have come face-to-face with the inherent challenges involved with handling the wide range of fabric items found in a home. So let’s pull back the curtain and look at what goes into the professional restoration of garments and textiles.

A dedicated textile restorer maintains a facility with an investment of hundreds of thousands of dollars in equipment. Many jobs require drying with blowers and dehumidifier units. Others call for deodorization equipment such as ozone or hydroxyl machines. Then there are the actual cleaning equipment options, broken down into wet cleaning and drycleaning.

For garments, restoration procedures are dictated initially by Care Labels, which are required by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) for the method of safe care. Specialty items such as leathers, suede, furs, window treatments, shoes, luggage and rugs each requires its own specific approach and treatment, oftentimes involving hand-cleaning with cleansers specially-designed for the type of material.

A modern textile restoration facility will include machines that are based on various solvents. For years, perchloroethylene (perc) was the standard drycleaning solvent. While very effective at cleaning, perc has been banned in certain states. As a result, a new generation of solvents has emerged, including hydrocarbon, petroleum, liquid carbon dioxide and silicone-based solutions. With each of these, an in-depth knowledge of chemistry is required in order to regulate the solvent temperature and concentration, based on the type of machine and contaminant.

According to Mike “Stucky” Szczotka, industry consultant and technical advisor to CRDN, recent advancements in equipment and technology have led to an increased combination of water-based and drycleaning, along with the introduction of industrial-strength high-extraction washers and dryers, drycleaning machines using specially-formulated cleaning agents, presses, steam tunnels, flatwork ironers, finishing/tensioning equipment and more, all designed to effectively and efficiently handle enormous amounts of textiles.

The successful removal of contaminants requires customized treatment with four key components:

- Time

- Temperature

- Mechanical Action

- Concentration of Cleaning Agents

Higher laundering temperature, for example, reduces the surface tension of water and accelerates most chemical reactions, enabling cleaning agents to function more efficiently. Proper mechanical agitation creates uniform distribution of cleaning agents for enhanced soil suspension and a higher effectiveness of cleaning.

Beyond the wide range of equipment required, the key is experienced personnel who are trained to identify each type of material and to know what method of cleaning is best suited based on the type of contaminant.

On most losses, there are multiple levels of contaminant to consider. A fire loss, for example, will include odor, soot damage, water damage, and potential effects from nitric acid. Smoke produces two basic pollutants: oxides of nitrogen and carbon particles. When combined with moisture, the result is nitric acid. Within hours, fabrics can become discolored, and within days, fabrics may stain permanently. Smoke odor varies widely depending on the material burned, i.e., wood vs. plastic vs. protein vs. electrical, which is why multiple options are necessary for the deodorizing process that breaks up the smoke molecule to eliminate odor and prevent it from being set in the fabric. There is also the need to identify pre-existing damage to an item that wasn’t caused by the loss, which must be documented and factored into the restoration procedure.

With water losses, speed of response is crucial, as dye transfer must be prevented. Light colored wet items are separated from dark colored items. Dry-cleanable items must be dried before cleaning, and washable items should be washed as soon as possible to eliminate any chance of dye transfer or mold development.

The type of water damage also must be considered. Category 1 (Clean Water) originates from a source that does not pose a substantial harm to humans. Category 2 (Grey Water) contains a significant degree of chemical, biological or physical contamination, with the potential to cause discomfort or sickness if consumed or exposed to humans. Category 3, known as “Black Water,” is grossly unsanitary and contains pathogenic agents, arising from sewage or other contaminated water sources such as rising flood water from rivers and streams, and ground surface water flowing horizontally into homes. While drycleaning solvents have been proven to kill bacteria, fabric items from a Category 3 situation often are considered a “total loss.”

After items are electronically cataloged as part of a documented tracking system to create an audit trail, the restoration process often starts with the “spotter,” an individual whose expertise is to use the most appropriate pre-treatment on heavy damage or stains.

Dry-cleanable items then are transferred to a machine that uses a solvent instead of water for the cleaning process. The solvent contains little or no water, hence the term “drycleaning.” While solvent and water both wet fabrics, water “swells” fibers, and this swelling action causes shrinkage and dye fading. Solvents also are superior in removing oily or greasy residues.

Next, special dryers recapture solvent vapors and condense them back to liquid solvent for re-use, and an aeration cycle brings in fresh air to remove any traces of solvent. Air is drawn through a cold condenser or an activated carbon device (called a “sniffer”) to recover any solvent vapors which can then be re-used.

Finally, the items are “finished,” which involves steaming or pressing a garment to produce results similar to hand-ironing, which is particularly important for higher-end clothing. Each item then is electronically scanned to a location in a secure storage facility, which essentially becomes the insured’s “closet” until they are ready for delivery.

Overall, today’s textile restoration is vastly different from a retail drycleaning experience, yet there is still some “magic” behind the curtain, only it’s founded on science, skill and expertise, as well as all the right equipment.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!